"Food is Medicine" - But for whom? The accessibility problem in nutrition and liver health

This blog post is brought to you by EASL in recognition of World Liver Day.

Authors: Dana Ivancovsky-Wajcman and Jeffrey V Lazarus

Photo credit: Marjan Blan, Unsplash

“Food is medicine.” It’s a phrase we hear often in discussions about health and prevention and it’s the theme of World Liver Day 2025. The idea is simple: the right nutrition can help prevent and even manage chronic diseases, from diabetes to liver conditions like metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). But what happens when access to nutritious food is limited?

For millions of people worldwide, food insecurity makes the idea of using food as medicine feel more like a privilege than a practical reality. The issue goes beyond hunger—it’s about lacking consistent access to healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate foods. This challenge is particularly urgent in communities already facing higher risks of chronic diseases, including liver disease.

In fact, recent insights show how food insecurity and poor nutrition contribute to a “silent epidemic” of liver conditions, with obesity and unhealthy diets playing a major role.

If we’re serious about promoting food as a tool for better health, it’s time to confront the accessibility problem. Who truly has the option to eat for their health—and who is being left behind?

How does food insecurity impact liver health?

Food insecurity refers to inconsistent access to enough and/or nutritious food necessary for maintaining a healthy and active life. However, it is not solely associated with undernutrition; an individual may live with overweight or obesity while still experiencing food insecurity due to a diet dominated by low-quality foods. Ultra-processed foods, added sugars, refined grains, sugar-sweetened beverages, and alcohol have been shown to contribute to increased risk for MASLD incidence and deterioration, including higher odds for liver cancer.

“…an individual may live with overweight or obese while still experiencing food insecurity due to a diet dominated by low-quality foods.”

Paradoxically, low-quality foods are often more affordable and accessible, especially for vulnerable populations. Consequently, individuals with a lower socio-economic status face a greater risk of food insecurity and inequity. Beyond its metabolic consequences, food insecurity is linked to social stigma, self-stigma, and psychological stress—factors that further exacerbate health disparities. These challenges not only diminish quality of life but also contribute to the growing burden of metabolic diseases, including obesity, type 2 diabetes, and MASLD.

Why is healthy food less accessible for vulnerable populations?

Access to healthy food is shaped by more than just personal choice—economic, environmental, commercial, cultural, and social factors all disproportionately affect vulnerable populations.

Here’s why nutritious options often remain out of reach for those who need them most.

- Economic Barriers – fresh, nutrient-rich foods are often more expensive than ultra-processed alternatives, making them less accessible to low-income populations.

- Environmental Challenges – many low-income neighbourhoods lack supermarkets or grocery stores that offer healthy food options, creating food deserts and limiting access to nutritious choices.

- Commercial Determinants – aggressive marketing of unhealthy foods and alcohol often targets vulnerable populations, shaping their dietary choices and habits.

- Cultural Considerations – the absence of culturally appropriate healthy foods and limited nutrition education can significantly influence individual food choices.

- Social Inequities – factors such as income, education, and housing—can critically shape food choices and overall health outcomes.

What needs to change to make ‘Food as Medicine’ a reality for all?

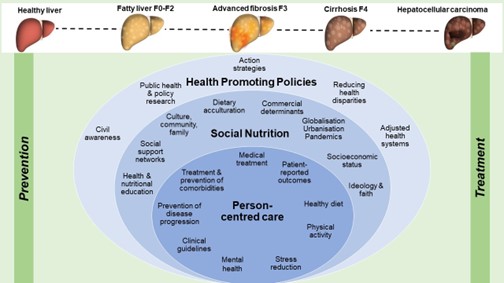

Making lifestyle changes and maintaining healthy habits is often challenging for everyone. However, vulnerable populations sometimes face even greater difficulties. Therefore, prevention and treatment of MASLD and related comorbidities should extend beyond the individual level to include social and policy-based interventions (Figure 1).

To implement those strategies both research and actions prioritisation are needed.

Figure 1. Achieving favourable steatotic liver disease outcomes via social

nutrition-informed preventive hepatology

As the image shows, implementing person-centred care, social nutrition and health-promoting policies in parallel is central in minimising health disparities and preventing and treating steatotic liver disease.

Conclusion